More schools are buying mobile ‘panic buttons’ for shooter scenarios

School districts around the country are equipping teachers with “panic button” apps, which officials say are making schools safer. Experts say, though, that while the apps might look like the future of emergency response, schools and government must tread carefully when adopting them.

Panic button apps abound in the public safety market, promising to put rapid, comprehensive emergency response into people’s pockets. They advertise to individuals, hospitals, construction workers, and myriad other consumers, but the apps have received particular interest from educators and school officials.

Many say they see the technology as a new and lifesaving defense against school shootings like that in Parkland last year, which have shaken the country and driven new safety measures in schools. Arkansas adopted panic button software in its schools statewide in 2015; D.C. schools did so last year.

In Oklahoma, which has invested $3 million in a panic button app to launch this fall for all its 537 school districts, getting the software “just seemed like a natural progression,” said Steffie Corcoran, the director of communications at Oklahoma’s Department of Education.

“Oklahoma is very interested in prioritizing student safety, and has been doing so for a long time,” Corcoran told EdScoop, adding that the app had been met with “really enthusiastic interest” from all sides. The Oklahoma’s Sheriffs’ Association endorsed the move, citing headlines from other schools in other states that credit the app with saving lives.

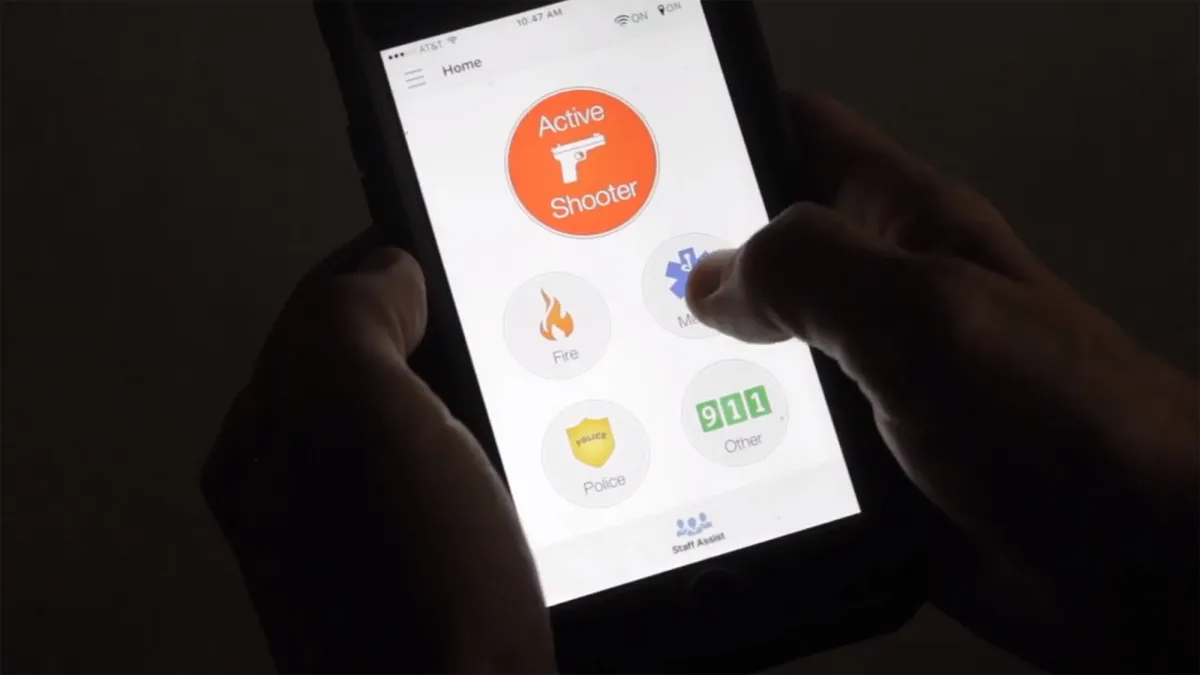

Oklahoma’s app is tech company Rave Mobile Safety’s “Rave Panic Button,” which Rave says is used by “thousands of entities” nationwide. The app actually has five panic buttons — when the app is opened, the user can choose the class of emergency. The largest button, in bright red, is for an “active shooter.” The other buttons send alarms for fire, medical, police, or other general emergencies.

When any of the buttons are pressed, the app dials 911 — and then sends alerts to chosen staff if the user is on campus. The 911 call center, through a web-based application, can see the caller’s location and information about the school, like floor plans and personnel. That’s only, though, if the center has integrated Rave’s call center software, which Rave says states and counties generally license with the app.

“The faster we can make people aware on a campus that they need to take action, the better the outcome will be,” Noah Reiter, Rave’s vice president of customer success told EdScoop. Even if “all the stars align” during an emergency 911 call, he said, there’s often still a lag before school administrators or other personnel are aware of the incident. He said the Panic Button is solving that problem.

Legitimate concerns

The Rave software is not the only app that is trying to fill up the gaps in emergency response. Mobile panic buttons have become something of a fad lately in the industry, says April Heinze, a director at the National Emergency Number Association. “It seems like every single day, we get a new app popping up saying that they can do something miraculous,” she said.

But those miracles aren’t always compatible with emergency response systems, Heinze said. “They see a need, they make an application, and then they ask, ‘Well, how is this going to work with 911?’ And most often, it doesn’t quite work,” she said.

It’s one of the reasons, she said, that if the apps aren’t cautiously designed and implemented, they can be ineffective.

The Rave software, Heinze said, doesn’t fall into most of the traps that bring down other public safety apps. The 911 dial is not routed through a different number, nor does it attempt to directly contact emergency responders — two well-meaning features of some apps that Heinze said can breed confusion and cost time. The app doesn’t try, either, to attach extra information to the call that most 911 call centers can’t receive. Reiter calls those concerns “legitimate,” and says that Rave has worked hard to mitigate them.

“They’re one of those innovators that work really hard to make sure what they’re creating is useful and beneficial to the 911 community,” Heinze said of the company. When innovators do that, she said, the apps can bring “tremendous value.”

Future of emergency response

But without proper training for dispatchers on how to use software like Rave’s, the apps can still easily overburden emergency response centers, Heinze said, as they pile on new features and notifications that dispatchers must attend to while they field calls. “It can be detrimental,” she said.

And a more fundamental challenge of the apps, Heinze said, is that novelty often doesn’t do well in emergency situations. “A lot of times, you’ll see in places that have these applications that [users] won’t even think about pushing the button,” she said. “They’ll just pick up the phone and call 911, because that’s what we know how to do.”

The emergency response world is divided on whether such apps are the future of emergency response, in schools or anywhere else. “In the long run, it could be — the key word is ‘could’ — be a part of next-generation 911,” Heinze said, referring to nationwide efforts to replace the outdated, copper wire systems of most 911 call centers with digital platforms that can handle video and images.

Reiter disagreed, saying he does not see the company and its Panic Button as a temporary fix for 911, but rather part of a careful vision for its future.

“In Rave’s view of the world,” Reiter said, “we’ve been providing next-generation-like information long before next-generation 911 ever was implemented.”