AI detectors are easily fooled, researchers find

New research from the University of Pennsylvania shows that many AI detectors are easily fooled with simple tricks and that many open-source models for detecting AI content use “dangerously high” default false positive rates.

One of the study’s authors, Chris Callison-Burch, told EdScoop that one upshot of his research is that professors should think twice before accusing students of unethical behavior.

But the findings are also more widely pertinent for a society that swims in an increasingly polluted sea of information. As totalitarian nations use generative AI tools to aid their propaganda campaigns and as bad actors use them to make their phishing emails and election misinformation sound more convincing, the value of a tool that can accurately validate human-generated content grows.

Callison-Burch, who teaches UPenn’s popular AI course — he said it attracted 600 students last fall and that he expects this fall to be the same — said some of the AI-detection companies’ claims don’t match his research findings.

GPTZero advertises itself as producing the “most precise, reliable AI detection results on the market.” ZeroGPT bills itself as “the most Advanced and Reliable.” And Winston AI claims “unmatched accuracy” with a “99.98% accuracy rate.”

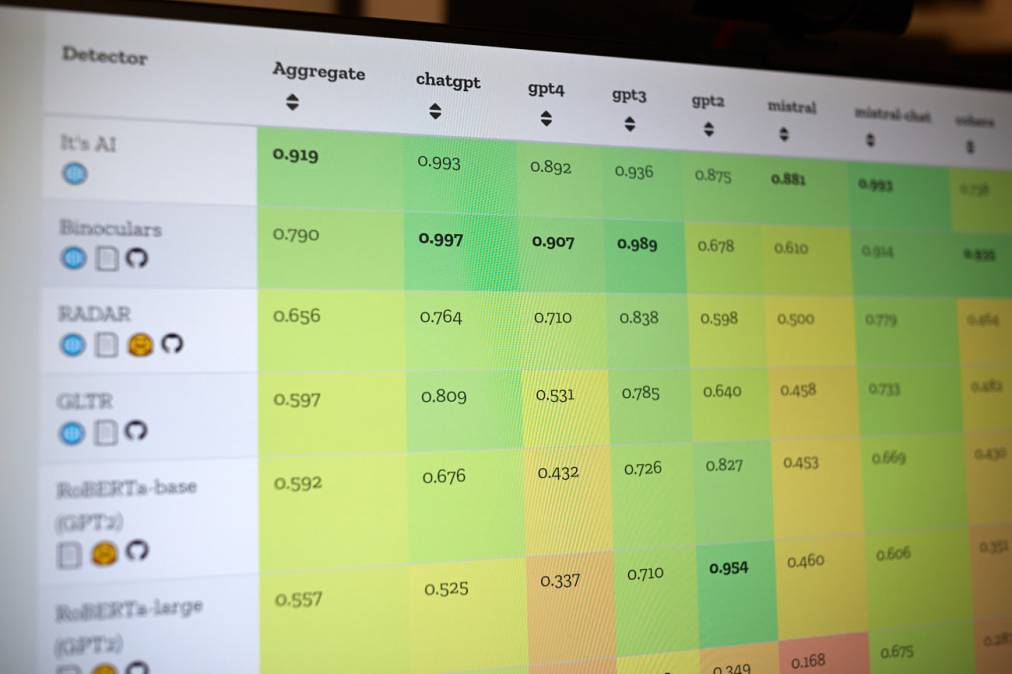

While researchers found that most private companies studied had calibrated their models with sensible false-positive rates, the same wasn’t true for many tools that use open-source models.

Callison-Burch said the trouble with accuracy rates is that they often neglect false positives: Anyone can catch 100% of AI-generated content if they’re willing also to flag all or most human-generated content as being AI-generated, for instance. He and his team found that adjusting models’ false-positive rates to what he called a “reasonable” level greatly reduced the ability of the models to detect AI-generated content.

“These claims of accuracy are not particularly relevant by themselves,” he said. “… I would use these systems very judiciously if you’re a professor who wants to forbid AI writing in your classrooms. Probably don’t fail a student for using AI just based on evidence of these systems, but maybe use it as a conversation starter.”

Another finding was that some of the most accurate detectors sometimes fail outright when faced with technical challenges that wouldn’t bother human evaluators. Researchers tested detectors against a series of “adversarial attacks,” such as adding whitespace to the text, introducing misspellings, selectively paraphrasing, removing grammatical articles and using homoglyphs, characters that look the same or very similar to ordinary letters or numbers, but that computers register as distinct.

“That breaks these AI detectors and their performance drops by like 30%,” Callison-Burch said of homoglyph attacks. “So if you’re a student and you want to get away with cheating, just add a bunch of homoglyphs and the teacher reading the essay is going to think it looks fine.”

Researchers also found that AI detectors usually struggle to generalize across different AI models. Callison-Burch said that most detectors are good at identifying content created by ChatGPT, but that feeding them content generated by any number of lesser-known large language models can crush detector performance.

Callison-Burch’s work isn’t only academic. He said he hopes this work will help open-source projects and private companies develop more-effective tools. His team published the dataset it used to test AI detectors — containing 10 million AI-generated texts — to be used as a standardized benchmarking corpus. Results are published on a public leaderboard, which is currently topped by a project called It’s AI.

“Perhaps this can make the claims that people are making more scientific,” he said.

Since the public release of ChatGPT in November 2022, many university students have claimed they’ve been falsely accused of cheating with generative AI — so many that The Washington Post last year published an article with tips on how students could defend themselves. It encouraged students to point out that essays on technical topics are more likely to be flagged as AI-generated because there’s less room for creativity when describing facts about engineering or biology, for instance. It also urged students to point to high-profile failures of AI detectors, such as GPTZero’s assessment that the U.S. Constitution was written by AI.

Although cheating is top of mind for many faculty and administrators in higher education, it’s only one mischievous use of generative AI. Callison-Burch, who’s been studying AI and natural language processing for more than two decades, said generative AI has exceeded the capabilities of what he thought he’d see in his lifetime, and that its influence is being exerted everywhere online, from e-commerce sites to scientific communities, where it can aid fraud.

“In some ways it’s a bit of an arms race,” he said. “People who want to cheat are going to come up with some clever new way of hiding their ChatGPT-generated text and the detector companies are going to have to continuously improve their systems to buffer against those.”