ChatGPT is about as exciting as a Twinkie

As a professor at the University of Southern California Rossier School of Education, my expertise focuses on how technology can be used to learn better, faster and keep us motivated to continue engaging with learning. Given this, you would think that I would be incredibly excited about the innovation that ChatGPT will enable, both broadly and in educational settings. Surely students will cheat (learn! I meant learn!) better, lawyers will lawyer better and journalists will write better… right?

Wrong! I don’t particularly care about ChatGPT.

Why? Because ChatGPT is no more revolutionary than the TV dinner. Yes, its affordances are novel, but once that novelty wears off, we will be left with a fast word writer. Who cares? While speedy work is great and can be a means to iterate toward innovation, it is meaningless without guidance from someone who knows what they’re doing. Writing is not simply “content” — it is a form of human expression. That’s true for both an author finishing a novel and a seventh-grader writing an essay. I read what they’ve written because I care about what they have to say.

Good writing is authored, not generated. Writing that I want to read from my students shows me how they think and why they think. Understood this way, writing is best considered as an asynchronous conversation. This is especially true when I am helping to develop the writing of my students.

In this age of accelerated commodification, many seek faster ways to churn out content that will be consumed by others in the hopes of getting more eyeballs on screens. I don’t blame folks for being excited about ChatGPT and its efficiency, but it’s like the excitement caused by mass produced foods that came into fashion in the mid-20th century. Canned meat you say? Twinkies? I don’t see wide-eyed folks marveling at the processed foods on supermarket shelves. The hype train for Spam has come and gone. So too will the excitement generated by ChatGPT be tempered over time until we are left with whatever use-case survives the current gold rush.

And when I read, I don’t simply want canned words — I want a full literary meal.

Music provides another analogy. Do you only listen to remixes or do you seek out new and interesting songs, genres and artists? Remixes have their place, but I wager that most people enjoy hearing new songs by their favorite artists. Humans enjoy the discovery of new sounds, new lyrics — new expression. That is why I am not worried about ChatGPT and why everyone needs to calm down about it. Unless your labor can be reduced to remixes of your previous work, then you have nothing to worry about.

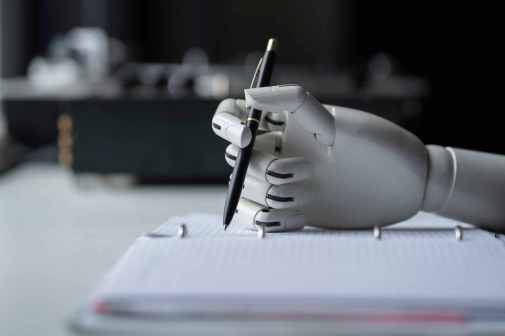

When I think about how ChatGPT can be used for learning, I think about how much of what we expect of students has been reduced to mere content creation. Some of this has occurred because it’s more convenient to evaluate that kind of writing. We ask students to summarize something so that we can quickly skim it to make sure there are no glaring mistakes. Or worse, we linger on mechanics at the expense of engaging with their written expression. When our expectations are so reduced, why wouldn’t the market respond by automating such tedious writing? If we want what we already know to be reflected back to us, then writing an algorithm to do it seems like the most efficient and logical solution.

Still, there is potential for ChatGPT in education. For younger students, perhaps it can be used as fodder for a debate with an artificial antagonist. Instructors can ask their students to use ChatGPT to take a position so that they can then take the opposite position. This would enable and encourage critical reflection, just as chess players use engines to improve their game.

For my fellow professors out there: If you are worried about ChatGPT being used to cheat, I urge you to climb up Bloom’s taxonomy and assign work that forces your students to think. Work that yields prose that you want to read. Think carefully about the type of asynchronous conversation you’d like to have with your students.

Pose hard questions! Ask students to find the weaknesses of AI generated prose. The fundamentals of good writing haven’t changed — we’ve just added another tool. With the development of any new tool there will always be those who overgeneralize its usefulness. I urge you to not be such a person, because while ChatGPT is positioned to be a great tool, it is not positioned to replace true authorship.

Disagree with me? Write about it.

Stephen Aguilar is an assistant professor at the University of Southern California Rossier School of Education and the associate director for the newly founded USC Center for Generative AI and Society.