How Clemson keeps cryptominers off its supercomputer

When a number of nodes on Clemson University’s Palmetto supercomputer were at peak processing capacity even though no students, faculty or researchers were using them, IT systems architect Nitin Madhok knew something was wrong.

“They weren’t doing anything, and yet its CPU and memory usage was always at 100 percent,” said Madhok, who’s been with Clemson since graduating from the university in 2013. “It wasn’t going down even when they weren’t doing any work. That was kind of unusual for us.”

The unusual traffic data originally first spotted last year pointed to cryptomining as the reason for the computer’s constant CPU usage — a process by which the computer’s processing power is used to earn a kind of cryptocurrency. While the IT security staff at Clemson couldn’t initially figure out exactly why the CPU usage was so high, just noticing the trend was enough to prompt an investigation. Splunk, a data analysis software firm that tracks patterns in regular computer and network processes, helped Madhok and his team solve the mystery in the following days.

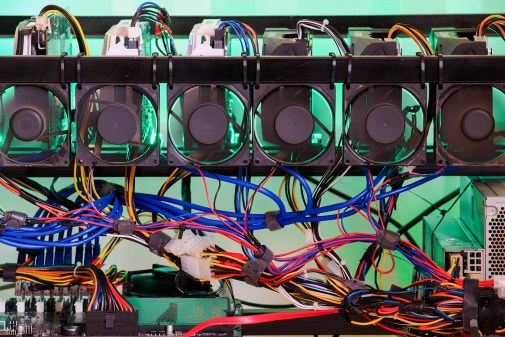

Palmetto, Madhok said, is one of the five most powerful supercomputers at public universities nationwide. That means it can run programs faster and more often than regular computers. That makes it an enticing target for people who mine for cryptocurrency, because more processing power means more income, said Scott Helme, an information security researcher and founder of report-uri.com, a free website-scanning security tool. ”

However, using a university-owned computer like Palmetto to mine cryptocurrency is a violation of campus policy and the South Carolina State Ethics Commission — neither students or faculty are allowed to use a state resource for personal financial gain.

Cryptomining efforts are popular across higher education, according to a study published in March from Vectra. The California-based cybersecurity company revealed that 85 percent of cryptocurrency mining instances happened in higher education between August 2017 and January 2018, compared to just three percent in the technology sector. The most recent high-profile scheme hit universities worldwide in February through a vulnerability in a browser widget to mine the cryptocurrency Monero. It’s hard enough for universities to monitor cryptomining on student-owned laptops, but in Clemson’s case, a supercomputer presented unique challenges in network defense.

Manually monitoring Palmetto would have been virtually impossible, Madhok said. He and his team could have collected the CPU and memory data on what processes are running, and the data from network packet aggregators showing the increased traffic, but that only told part of the story, and they needed answers — why was it running so hard?

‘Intensive’ research

In 2017, Madhok and his team licensed Splunk for enterprise security across Palmetto and Clemson’s general network. The university’s other security services —Bro, an intrusion detection system, and and Gigamon, a network monitoring software, fed data like network packets, the logs from the servers, metrics like CPU and memory storage performance into Splunk. That raw data held the answers Madhok was looking for — without Splunk, though, it was virtually impossible to understand.

The “machine-generated data” fed into Splunk, said Jennifer Roth, the company’s higher education lead, is typically unstructured data that doesn’t “fit nicely” into traditional rows and columns — information from network switches, servers and other devices. Because of that and the sheer quantity of data that Palmetto creates, it’s hard to detect anomalies within it, and even harder to pinpoint the cause. Once fed into Splunk and organized, however, the data analysis software pointed Madhok to cryptomining.

The way it works, Madhok said, is by finding correlations within different metrics and data streams. Bro and Gigamon, he said, are “smart” enough to feed information into Splunk — meaning Madhok has data from the server itself on what the server is doing. If Splunk shows that memory is spiking on a server but his staff notices there’s no processes running at that time, that’s fishy, he said. Likewise, if the intrusion detection system finds a network packet that originated from a server with “crypto” in its name, Splunk flags that server and notifies the IT staff.

Without the malware detection capabilities of those services, though, he says it would have been difficult to pinpoint the problem.

“If you’re expecting a supercomputer to be doing very intensive processes — and cryptomining fits that bill — then it just depends on the level of scrutiny you have [if you’re able to detect it],” Helme said. “If a supercomputer is very busy doing something, that might look very normal.”

The discovery of cryptomining, Madhok said, wasn’t a total shock — he and his staff were aware of how common a phenomenon it was in higher education, and informed the student whose account was attached to the mining that they had been hacked. The student, like many others, Madhok said, had no idea their account was mining cryptocurrency. The student’s claim is supported by the fact that the “significant amount” of Monero that was mined was never exchanged; Madhok said he could ensure that by monitoring DNS queries with the keywords like “coin” or “crypto.”

Ultimately, most Palmetto users, including faculty and researchers, aren’t aware their accounts could be used for illegitimate purposes until the SOC notifies them that their accounts have been compromised and access is temporarily revoked.

But, Madhok said, schools can’t absolutely prevent users from mining cryptocurrency — the malware will always be available to download and there will always be a workaround bad actors can use. Because of that, he said, the solution is to be proactive by establishing a security environment, like Clemson’s, that can give administrators visibility of their networks.

“It’s not necessarily a question of whether you can prevent it,” he said. “It’s a question of how fast you can respond to it.”

Madhok said he sometimes finds students mining cryptocurrency on their own laptops — he gets those notifications through Splunk too — but he can’t stop that, because they’re not on a state-owned resource or using a public website to do so. But for those who have mined on Palmetto, he said a warning, temporarily blocking access and some education on good internet hygiene have sufficed.

This story was updated on December 5 to clarify the SOC’s notification and revocation process for compromised student and faculty accounts on Palmetto.