One professor’s obsessive quest to replicate the university classroom experience from his home studio

When the image of Sean Willems comes in over Zoom, he’s ebullient, sharp and engaging — not as much as he would be in person, but that’s not an option right now.

A tenured business analytics and statistics professor at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville, Willems knows from his two decades of teaching just how important his presence is as he attempts to connect with students in the classroom. And when he was told in April, as a visiting professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, that classes would go fully online for the summer, he devised a plan to preserve as much of the in-class experience for his students as possible.

Undertaking a project that he admitted is “crazy” and perhaps “a little obsessive,” Willems in May began converting a room in his house into a video recording studio from which he now streams online classes that go beyond the production quality and sophistication of what any other professor is offering today. Armed with little knowledge and no interest in the technology required, he said he spent tens of thousands of dollars and more than 300 hours building the studio.

“I have zero interest in this stuff. I’m an academic,” Willems told EdScoop. “I have no interest in photography. If I move the camera eight inches, it takes me four hours — I’m not kidding — to reset the shot and reset where I need to stand and the perspective and everything.”

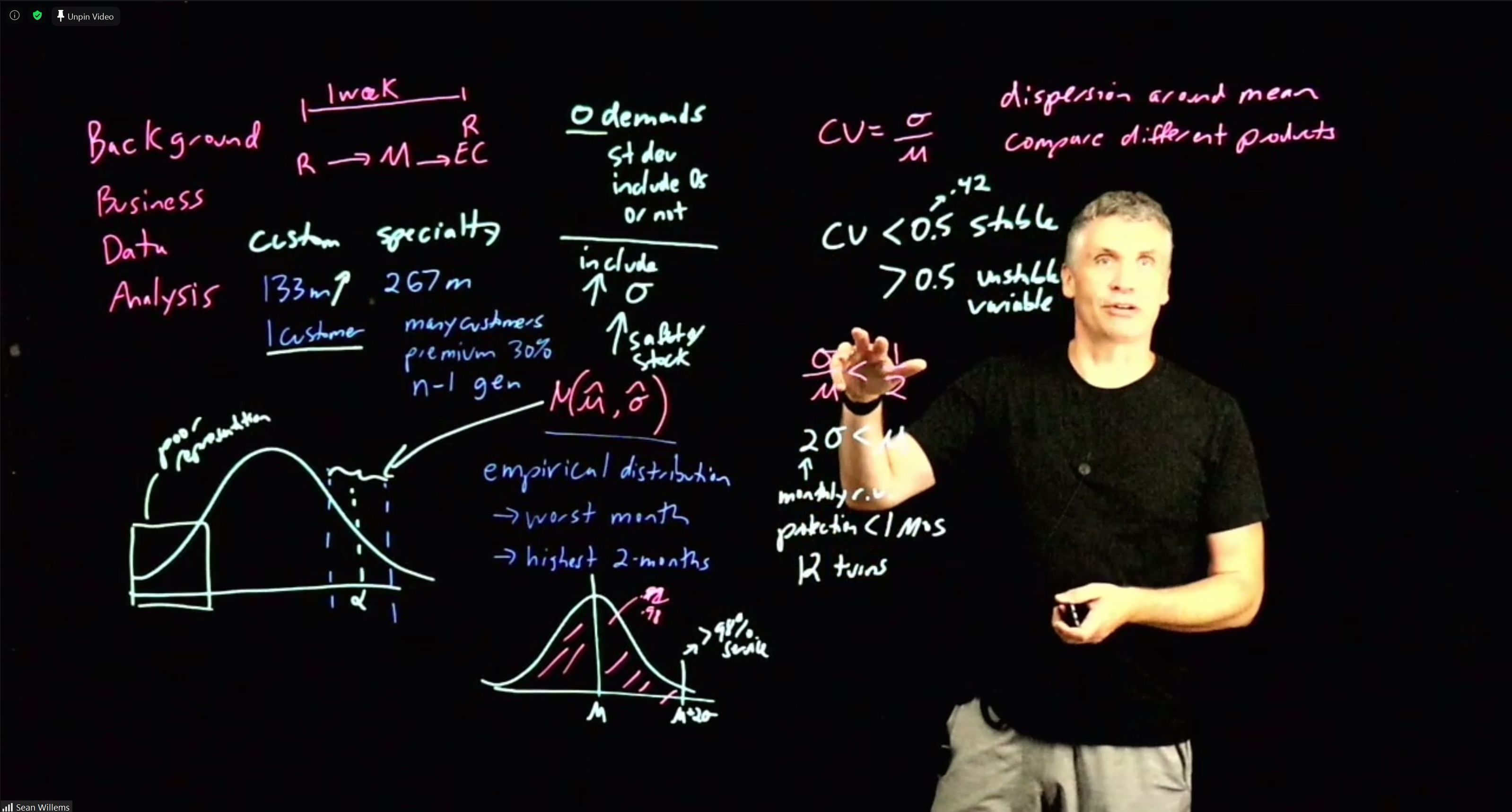

This is what students in Willems’ classes see when they tune into his Zoom channel.

As Willems delineates in a paper published on his website, he threw himself into the project for reasons of curiosity — “pushing the boundaries of what a home studio is capable of doing,” he wrote — and a recognition that the default technologies available to educators, of consumer webcams and laptop microphones, are not reasonable replacements.

The universities where professors have resigned themselves to these common tools are the same that stake their reputations on claims of being world-class learning institutions. The pandemic’s constraints undermine, for example, the educational mission of MIT, which states on its website that its undergraduates can work “shoulder to shoulder with faculty” as they “topple conventional walls between fields in the push for deeper understanding and fresh ideas.”

Dozens of lawsuits filed against universities this year bear out this evident mismatch. Students across the country are claiming that Zoom classes, which often come with muffled audio and distinctly unprofessional lighting and video, are a poor replacement for the in-person classes and life-altering social experience they signed up for when they agreed to take on tens of thousands of dollars in tuition debt. A suit against New York University claims that the current online learning options are “subpar in practically every aspect.”

Students who take Willems’ classes may not get any shoulder contact with professors, but avoiding a subpar learning experience is in fact his explicit mission.

“I always tell students we’re going to be working incredibly hard to get back to zero,” he said. “That sounds terrible, but that is what this is. This is an incredible amount of work to get us back to zero. If I was just doing my normal teaching, I could have basically just arrived in the classroom and taught, just like I normally do. Now it takes me hours of prep just to get a point that approximates that — isn’t better than it — approximates that.”

His classes, which cover topics like operations management and supply chain analytics, may not be in-person, but Willems’ 420-square-foot studio can at least partially circumvent many of students’ common pedagogical gripes with the online format. He started with a $3,000 85mm lens from Canon and said he built the rest of the studio around that first piece of equipment, which helps students see “the nuances of teaching.”

A standing desk allows him to teach in his usual manner: standing. An omni-directional microphone ensures he can be heard with high fidelity as he moves about. A console lined with buttons allows Willems to seamlessly switch among various teaching views, or “modalities” — he can show documents or jot neon-colored notes from behind the pane of a lightboard, which is automatically mirrored in the students’ view so he doesn’t have to write backward.

Willems demonstrates the lightboard in his home studio.

A tightly controlled lighting set-up, complete with room darkening gear, ensures the picture isn’t blown out when he transitions between modalities or brings up a particularly bright slide. And the prime Canon glass that served as the starting point for his project, which produces a silky bokeh effect in the background when he’s speaking directly into the camera, tracks focus when he steps back to pull a book from off the shelf behind him, just as it might for cinematic effect in a Hollywood film.

“That’s a cool moment for the students, but really I think the benefit to them is all of the steps where I instill in the picture in a way that mimics the classroom,” he said. “There certainly initially is a shock-and-awe aspect of the studio. At an immediate level, there’s an appreciation for it, but if that was it, it wouldn’t be worth it, and the students wouldn’t find it worth it.”

If his expensive and time-consuming project was worth it, Willems said, its value comes not from its novelty but from removing the usual barriers and annoyances of technology so that he and his students can focus on the learning material. A large monitor allows him to survey his students as he teaches, but he said he still misses critical visual cues ordinarily relied upon by professors to guide lectures.

“The biggest one it misses is the ebb and flow that happens in the classroom,” he said. “When anyone teaches in class, they don’t teach at a constant rate. They speed up over things that students really get. They slow down over things that the group seems to think is more interesting. In Zoom it’s actually much harder because while, yes, you can put them on a big monitor like I’ve done and you can see them and you can see some level of engagement, and certainly you can poll them and these things, but it’s not the same as in a classroom where you see someone lean in or you see someone push back or you see someone look forward.”

This social disconnect has a few effects, he said, with an obvious one being that it takes him longer to cover the same amount of material. He now needs 95 minutes to teach an 80-minute class, he estimated.

There are other time burners, too, even with a rig as honed as Willems’. “Everything takes longer in the online synchronous format,” he wrote in his paper. “We invariably lose 30 seconds each class when someone fails to unmute.”

His paper outlines many other challenges. He wrote that his teaching assistant is essential — an “air traffic controller” — who ensures classes run smoothly, in-person or online, but that the online format soaks up far more of the TA’s attention.

“The TA arranges who talks next, keeping track of who has already talked and who has not yet talked,” Willems wrote. “The obvious downside of online learning from the TA’s perspective is they work much harder during the class session. The less obvious downside is they remember virtually no content from the online class itself. They are simply too busy managing the participants to pay any attention to the actual material being covered in the class.”

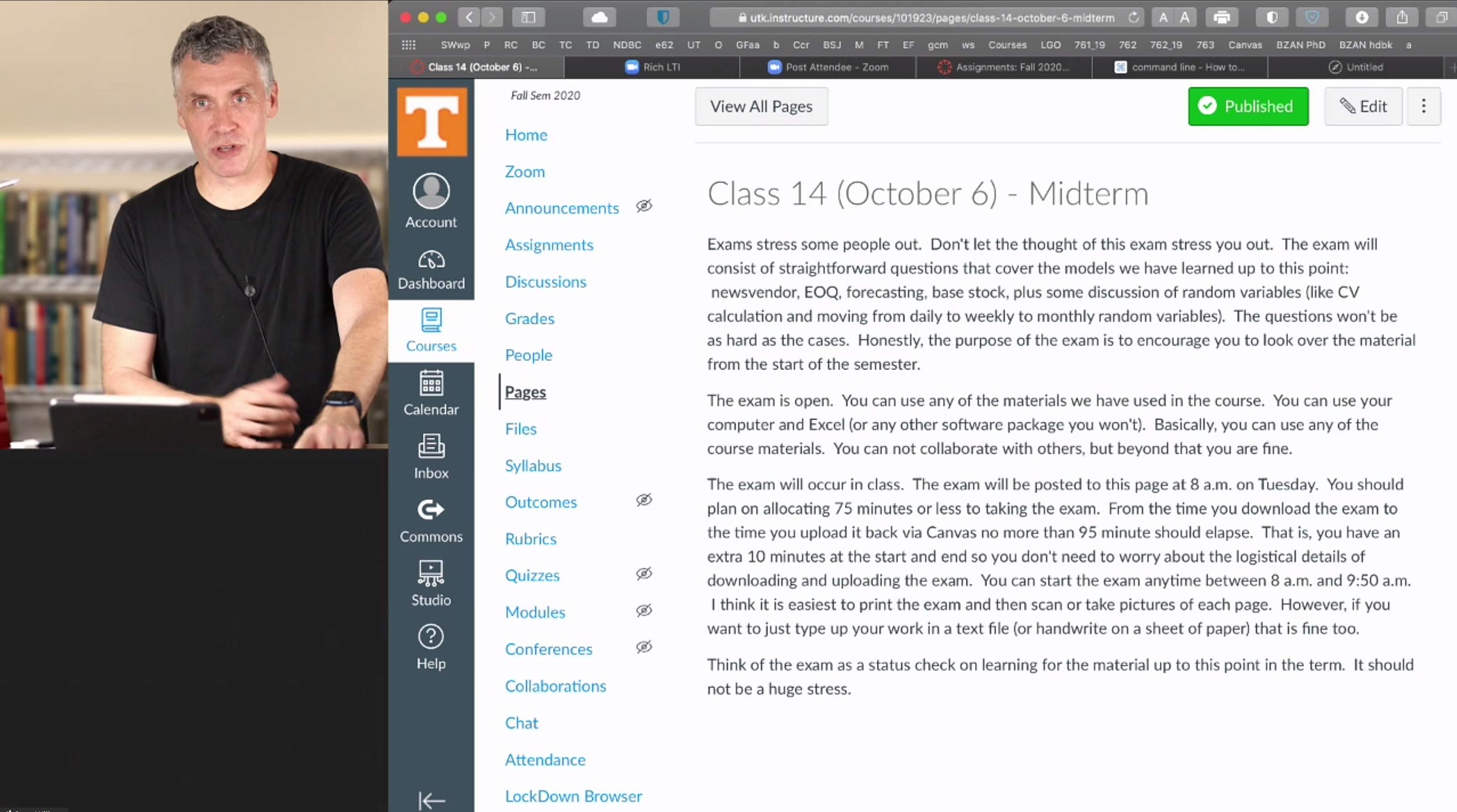

Willems can quickly adjust the size of his own camera view to make room for content being presented through a computer or a nearby document camera.

Technology can also present social challenges that require additional legwork to ensure no one’s feelings get hurt, he said. “At some point in most classes, the professor has to cut off or redirect a student who is saying something that is off-topic,” he wrote, adding that it’s harder to gauge a student’s reaction to such incidents online. “We address this by over-communicating with students after class.”

In sharing his paper with other professors, Willems said he hopes to encourage others to do as he’s done, and several other professors have built their own home studios based on his advice. It doesn’t have to cost thousands of dollars, he said, and his paper outlines a basic set-up that he said costs about $800 and can vastly improve the quality of any online class.

“To me, the students have invested, they want to learn, they want to come do it, so it makes it fully worth it to make the investment,” he said.

His paper also includes advice, with a top recommendation being that professors should use software, like Open Broadcaster Software, to scale up the size of their bodies in the picture frame so the image approximates the scale of a professor standing in front of a chalkboard, rather than a billboard. Another key recommendation is to be mindful of video and sound quality as students prepare to spend dozens or hundreds of hours listening to lectures.

“As faculty, I don’t think we think through, hey, people are actually staring at us,” Willems said. “I think what people like [about my set-up] is there’s a lot of resolution.”

And though he’s received favorable reviews from students, they still come with qualifications.

“I think the course did a good job adapting to the digital format although the cases were still not as stimulating as they would have been in person,” one MIT student wrote in a post-class review.

Willems said he agrees with that student, adding that he longs for a return to the university campus and an end to his days as a reluctant audiovisual gearhead.

“One of the most amazing parts of a faculty member’s job is that you have rebirth three times a year: You have fall, summer, spring,” he said. “It’s my favorite part of the job. And now you don’t get that. Every day is like every other day, honestly. It feels like an endless grind right now and so I’m going to be very excited when we’re back on campus.”