Database of 7 million syllabi pulls back the curtain on higher ed

Researchers at Columbia University released the second version of the Open Syllabus Project last week, a database of nearly seven million syllabi from 2,500 universities. The project, they say, is using big data to crack open higher education for the public.

The Open Syllabus Project released its first syllabus database in 2016, but last week’s updated version is more than five times the size of the previous, and has new visualizations and analytics. It represents roughly 5 percent of English-language curriculums in the last decade, researchers guess, although its collection is skewed towards the U.S., the U.K., Canada and Australia.

The project provides such an extensive digital look at higher education, its creators say, that they aren’t sure of all its applications yet. “It’s just been a continuous process of understanding how this data fits into this ecosystem of teaching and publishing,” Joe Karaganis, the project’s director and vice president of a think tank at Columbia, told EdScoop.

He said he’s realized the project is “a kind of skeleton key” to higher education — unlocking data and resources that have previously been restricted to institutions.

“Higher education’s kind of a black box. You approach it with a grasp of the reputations of the institutions you’re interested in. But other than what can be a very arbitrary experience browsing around a university website, there’s no real way to know what the contents of that education will look like,” Karaganis said.

With the syllabus project, that’s changing, he said. “We’ve begun to pull back the curtain a bit,” he said.

The Open Syllabus Project isn’t the first attempt to use syllabi to map out curricula and academic fields. Many colleges keep their own syllabus archives; libraries, in turn, have historically used syllabus analysis as a tool to look at courses.

But it was only in the last few years, Karaganis said, that technologies became cheap and advanced enough to support an endeavor on the scale of the Open Syllabus Project — which must sift through masses of data, picking out book titles and fields of study accurately from millions of documents.

The project cross-references the syllabi — which it gathers by crawling through university websites — to its own catalog of 80 million books and other publications, pulled from the Library of Congress and other sources.

What the project fishes out is more useful, searchable metadata — such as what titles are taught in certain courses, when, and how often. The previous version of the database sparked some controversy when, in 2016, it revealed that Karl Marx’s Communist Manifesto was one of the most-taught titles in higher education. The new version of the project, Karaganis said, offers data that shows that this is because Marx is commonly assigned in history and politics courses, not because of left-leaning economics courses, as some news outlets claimed.

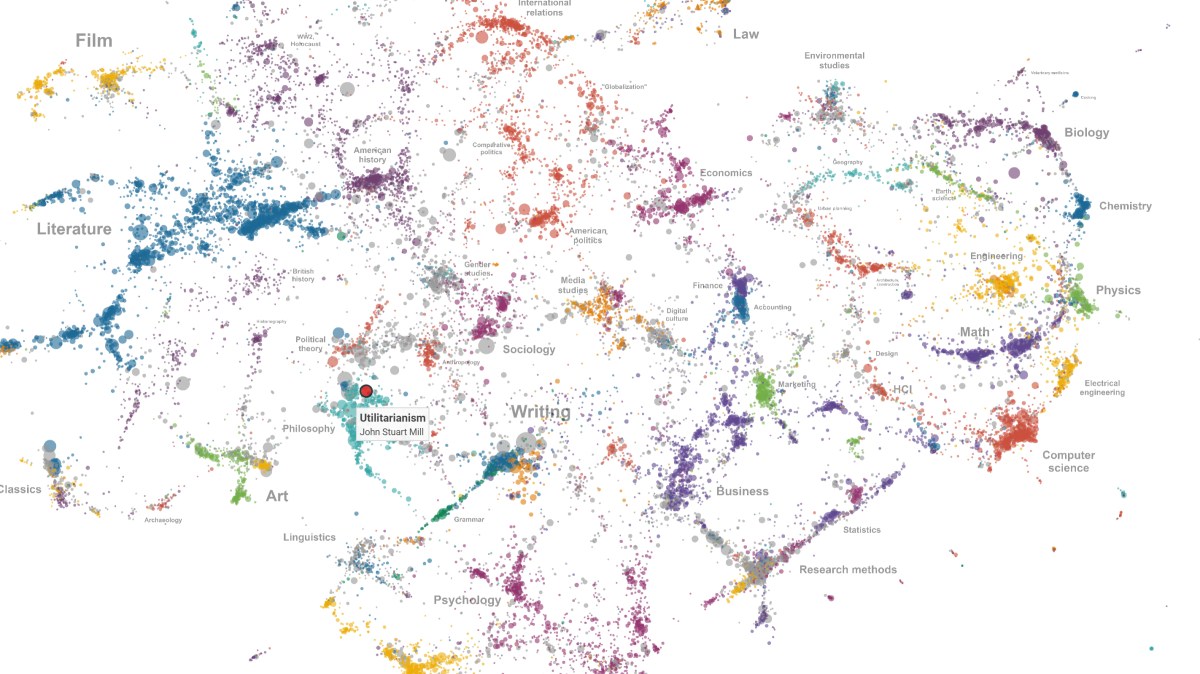

The project now displays a “galaxy” visualization tool which makes the syllabi into constellations, mapping out how fields of study are related to each other based on their shared titles. Marx’s dot, here, sits among the stars of sociology and political theory. Clusters of titles in more specialized fields, like music or law, are isolated from the rest.

Mapping out academia’s fields and subfields is one of a host of uses for the Open Syllabus Project, which has been featured on quiz shows, used to make listicles on higher education’s most-read books, and helped teachers guide curriculums.

It’s also, though, been swept up in the push for open educational resources, reaching students removed from U.S. colleges and universities. Within months of the project’s initial release in 2016, Karaganis said, about half of its web traffic was coming from developing countries. And the project now has a filter that allows users to search for textbooks that have open licenses.

“The syllabus project, just by listing the content of American education, served as a kind of proxy for it in ways that a lot of people found very valuable,” Karaganis said. It’s just one of the futures for the project that has emerged from the data, and, Karaganis said, he expects there to be many more.